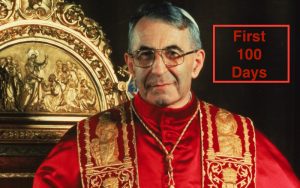

First 100 Days

In my last blog, I talked a bit about the scandalous goings-on in the Vatican duri ng the 1980s that influenced my depiction of events in the This Generation Series. And I thought in this blog, maybe we could take a bit of time to discuss a relatively unknown figure from that time, Pope John Paul I, Albino Luciani.

ng the 1980s that influenced my depiction of events in the This Generation Series. And I thought in this blog, maybe we could take a bit of time to discuss a relatively unknown figure from that time, Pope John Paul I, Albino Luciani.

Luciani grew up in a poor family in the mountains in the north of Italy. The entirety of his life as priest, bishop, and cardinal was devoted to helping the poor. Regardless of his station in the church, he viewed himself as first and foremost a pastor, even requesting that people refer to him as pastor rather than pope. In his days as Cardinal of Venice, he eschewed limousines for his bicycle because he loved to be among the people. Some examples of his character:

- While pope, he answered his secretary’s phone one day, saying, “I’m sorry the pope’s secretary isn’t here at the moment. Can I help?” When asked who was speaking, he jovially answered, “The pope.”

- While cardinal in Venice, he led a movement of parish priests to sell parochial gold and precious objects to make money for a center for the handicapped.

- He scandalized the Curia when, after being elected pope, he refused the ceremonial coronation (as the political leader of the Vatican State) and only had Mass instead.

Importantly, while cardinal of Venice, he had experienced first-hand the fleecing of a local bank by Bishop Marcinkus and his mafia connections. Luciani entered the papacy with a very aggressive plan to drain the swamp in the First 100 Days. A brilliant man, he quickly came to the bottom of the financial shenanigans of Vatican Incorporated and sought its closure. He asked the previous pope’s Curia officials to retain their positions until he could make well-reasoned replacements, but in the meantime, he adjusted their bonuses downward to reflect the fact that they served Christ’s followers and weren’t some sort of religious elite.

He also took actions to ensure that the Church worldwide was focused on caring for the flock and preaching Christ. This put him in the position to deal sternly with Bishop Marcinkus’s friend Cardinal Cody from Chicago, a man who made the notorious Mayor Daley look like an altar boy. He also took issue with Catholic doctrines, which he felt created undo hardship on parishioners, such as the previous pope’s signature piece Humane Vitae that disallowed all forms of artificial birth control. He rejected the notion of Ubi Lenin, ibi Jerusalem (Where there is Lenin, there is Jerusalem), a Jesuit moniker to support communist liberal theology espoused in Latin America. Further, he telephoned the head of the Jesuits to announce that he would have a few things to say to the order about discipline.

He made himself known by such statements as “It is only Jesus Christ whom we must present to the world. Apart from this we would have no reason, no purpose.” But Luciani’s words were often not published by the Vatican press. Repeatedly, his remarks were replaced with Curia-sanitized sentiments often at variance to his intentions. Inaccurate reporting from the Vatican press corp was a pattern he intended to resolve.

In terms of the Curia (courtiers and administrative functionals at the Vatican), he found that they viewed themselves as an entrenched ruling elite not subject to the dictates of the faith or willing to move forward to a church that he intended to return to the parishioners. He set about to change things, to fix his own house.

With these ideas in mind, he met with his acting Secretary of State, Cardinal Jean-Marie Villot to move forward. He made the decision to force Cardinal Cody in Chicago into retirement; to fire Bishop Marcinkus from the Vatican Bank and send him back to America with one day’s notice; and to replace a number of key Curia personnel. Last on the list for replacement was Cardinal Villot himself. There was an evident pattern in his replacements. Within the confines of the Vatican, there were not-so-well-kept secrets that many in the Vatican hierarchy had become high level members of local Freemason groups, actions strictly and vigorously forbidden for rank-and-file Catholics. A curiosity of the Luciani’s new appointments is that none of them appeared on lists of those with Freemason contacts. All of the people replaced had been known to have Freemason involvement.

As providence would have it, Luciani became pontiff just as Michele Sindona’s and Roberto Calvi’s banking houses of cards were falling around them. They, with the help of Bishop Marcinkus, had absconded with too much and their ponzi scheme was disintegrating around them. Their only hope was that the trail of their crimes was largely contained in Vatican records unavailable to civil authorities in other countries. Their survival depended upon retaining Bishop Marcinkus as head of the Vatican Bank. Unfortunately at an earlier date, Marcinkus had run afoul of the new administration when he threw then-Cardinal Luciani out of his office when Luciani questioned him about suspicious banking transactions affecting Venice.

The new pope’s initial actions and promises of further draining such a hideous swamp brought him powerful enemies in the Curia, the Mafia, and among cardinals who led less than exemplary lives. On day 33 of his First 100 Day plan, he was found dead in his bed, just hours after he had discussed his plans with Cardinal Villot. For his part, immediately upon hearing of the pope’s demise, Villot pocketed Luciani’s medicine from his nightstand and pursued rapid embalming to avoid an autopsy in violation of local law. His actions led to the long-held belief that Luciani’s night-time medicine had been poisoned.

We are left only to wonder what good could have come from Pope John-Paul I, this man who:

- Was elected pope when no one had considered him a serious contender;

- Made a commitment to turn the Church back to the people;

- Had distain for the elitist attitude of the entrenched hierarchy;

- Wanted no part of and sought immediately to correct alleged unlawful activities in the Vatican; and

- Placed the needs of the common man above those in power to serve him.

Unfortunately he was done in by an entrenched bureaucracy that saw his every action as a threat to their privileged status. Unable to comprehend the need for a breath of fresh air in the stale politics that characterized the Vatican, they ignored his requests and used the press against him, but he persisted. When they found he couldn’t be contained, they killed him along with any chance to dismantle a hierarchy that stifled the hopes, dreams, concerns, and faith of parishioners in favor of an elite ruling class.

So, Albino Luciani’s papacy ended on Day 33 of his First 100-Day plan to drain the swamp. But that’s just history—at least I hope it is.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts